|

|

ACCOUNT OF A VISIT

And he chuckled, and clucked, "What a great Grinch trick! Troy, New York, December 23, 1823. When the Sentinel ran some jaunty holiday verses captioned "Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas," not even the paper's editor, Orville Holley, knew whom to thank, or guessed that this poem was destined for greatness. Submitted anonymously, it was not by one of Holley's regular contributors. Resisting the oblivion to which most nineteenth-century newspaper verse was quickly consigned, "The Night Before Christmas" (as it came to be called) reappeared in the New York Spectator only nine days after its Troy debut, in a text borrowed from the Sentinel, then in New Jersey and Pennsylvania almanacs for the 1825 calendar year, next in a literary magazine called The Casket, in 1826. A few years later, when the New York Morning Courier reprinted it, the now popular ditty of Saint Nicholas was said by some to have been written by Clement Clarke Moore, a Bible professor at New York's General Theological Seminary. That rumor was reinforced fifteen years later with the publication of Moore's Poems. By the time he died in 1863, aged eighty-four, Clement Clarke Moore was known from coast to coast as the father of Santa Claus, an accomplishment for which his name has been revered ever since. But there are people in my town of Poughkeepsie, mostly persons of Dutch descent, who are unhappy with Professor Moore for having laid claim to "Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas." In fact, certain local historians feel so strongly about this issue that they would like to see Saint Nicholas in heaven take Clement Clarke Moore onto his own reverend lap, flip him over, and let the man have it on the bottom with "the birchen rod" for which Saint Nicholas was once famous.

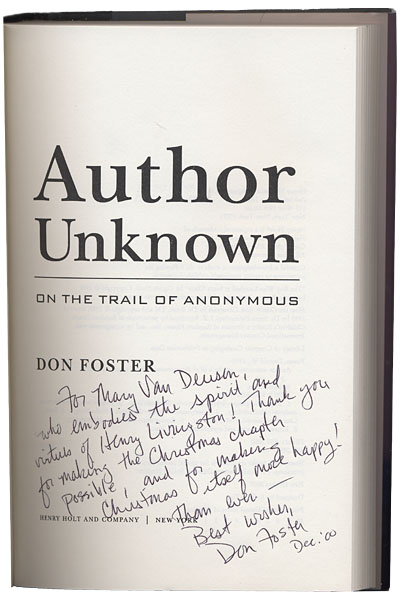

Poughkeepsie, New York, August 6, 1999 One hot summer afternoon I received a call from a resident of the Boston area, Mary Van Deusen, who identified herself as the great-great-great-great-great-granddaughter ("five greats") of Major Henry Livingston, Jr. Mrs. Van Deusen cheerfully explained that it was her ancestor Major Livingston, and not Clement Clarke Moore, who probably wrote "The Night Before Christmas." She was calling me, she said, at the suggestion of Professor Ian Lancashire of the University of Toronto. I stayed on the line, but only to learn why Lancashire, a distinguished Canadian scholar I knew, liked, and admired, would have given this woman my name. Ms. Van Deusen explained that she had no axe to grind. She was building a Major Henry Livingston, Jr. Web site. If I could show that "The Night Before Christmas" was written by her ancestor, not by Clement Clark Moore, that would be terrific. And if not, not. Mrs. Van Deusen chatted gaily on, telling me more about Henry Livingston and Clement Moore than I thought I needed to know. The two men, she said, were opposites. Professor Moore was a grouchy pedant, a student of ancient Hebrew who never had a day of fun in his whole life. In fact, he was against it. Henry, three-quarters Dutch, was immersed in Dutch American traditions. He was an artist, journalist, and poet; a surveyor and cartographer; an archaeologist and anthropologist; a flute playher and a fiddler; a free spirit and all-round merry old soul if ever there was one. Mrs. Van Deusen said that, in her opinion, the Major's poetry resembled 'Christmas' better than anything Clement Moore ever wrote. Most of the Major's comical and children's verses were written in anapests, just like "'Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house..." (-da-da-DUM, da-da-DUM, da-da-DUM, dada-DUM!). To demonstrate, she broke into a lilting recitation of some lines from a two-hundred-year-old verse epistle addressed by Major Henry to his younger brother, Beekman. I laughed when I heard it in spite of myself:

To my dear brother Beekman I sit down to write "That's just a sample." "I wish you good luck with your research," I said, "but..." "But listen to this: 'The Night Before Christmas' was first published anonymously in 1823. When it was ascribed to Clement Clark Moore in December 1836, probably by mistake, he said nothing. 'Christmas' became a huge hit. Moore remained silent - because the poem 'embarrassed' him. 'Christmas' was in print for more than twenty years before Clement Moore took credit. Now isn't that interesting!" "And did Major Henry take credit?" "No - but I can explain that. He was dead. Major Henry's children knew that Clement Moore didn't write 'Christmas,' that their father did, but no one would listen. I listened, but without much enthusiasm. Who but maybe Jabez Dawes would challenge the credibility of Clement Clarke Moore? Moore was a scholar, a Bible professor, unimpeachable, practically a saint himself, known to millions of Americans as the "Poet of Christmas Eve." His name by this time had appeared on millions of copies of "The Night Before Christmas." There was nothing to be gained professionally by becoming embroiled in a dispute over the true begetter of Santa Claus. Within academia, the inevitable response would entail such questions as these: "Who cares?" and "Why waste your time on the origins of an overrated piece of holiday doggerel?" From a professional point of view, this was a lose-lose situation. Responding not as a scholar but as a fan of Santa Claus from way back, I told Mrs. Van Deusen I'd give it my best shot. Pleased, she said she would also have to call Steve Thomas, which she had not done yet. "Steve Thomas!" "Yes. He has most of the original documents." My Steve Thomas was a detective with the Boulder Police Department. Mary Van Deusen's Steve Thomas was her distant cousin Stephen Livingston Thomas, a grandson of William S. Thomas, M.D., the Livingston heir who devoted more than forty years of his life to trying to prove that the Clement Clarke Moore attribution was a mistake. ...Mary Van Deusen drove from Boston to Poughkeepsie, taking up lodging at the Route 9 Holiday Inn, directly across from what used to be the Livingston estate and a short hike from Major Henry's final resting place in the Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery. The Major's property, called Locust Grove (named for its trees, not insects), is a state historic site, though not in honor of Henry Livingston Jr. Samuel Finley Breese Morse, husband to one of Livingston's granddaughters, acquired the land some years after the Major's death. Today, local schoolchildren who have no clue what a telegraph is can visit the home of the man who invented it. Situated opposite a bank, a motel, and apartment builds, the Samuel F.B. Morse estate does not feel like sacred ground. I had lived in POughkeepsie for fourteen years without ever knowing that Locust Grove once belonged to a Henry Livingston, and I had picnicked there without suspecting that it was viewed by some local experts as the birthplace of Santa Claus. My one poetical experience at Locust Grove was when I took my kids to see an outdoor production of Shakespeare's Macbeth, a violent affair in which young actors in army fatigues ran around the yard shooting toy rifles while my own boys sifted through the grass, looking for four-leaf clovers, bored silly. There had been no tingles, no close encounter with flying reindeer at Locust Grove, no intuition that something special took place on this plot of land. On the morning after Mary's arrival, I picked her up at the Holiday Inn and we drove to Clinton House, home of the Dutchess County Historical Society.

...I found it truly remarkable how much information was stored inside their heads [Mrs. Eileen Hayden and Mrs. Bernice Thomas, experts on local history from the Dutchess County Historical Society]. In a municipality whose official motto is "Poughkeepsie: 300 Years of People, Pride, and Progress," there is a lot of history to know, and these two women know it like no one else, in minute detail, from the first Dutch settler right on through to the First or even Second World War. But Mary Van Deusen and I were here to ask about "The Night Before Christmas." Mrs Hayden and Mrs. Thomas delivered their verdict crisply, with complete authority, and without hesitation: "That poem," they said, "was written by Major Henry Livingston Junior." Mary, who blithely agreed, introduced herself as a great-granddaughter (five greats, she added) of Major Henry. She said she had come all the way from Boston to investigate and to gather material for her Major Henry Livingston Jr. Web site. The archivists, though generally cooperative with requests to inspect original documents, were pessimistic in their assessment of Mary's enterprise. Several local historians had already written in Major Henry's defense - Benson J. Lossing (1886), Henry Litchfield West (1920), Cornelia G. Goodrich (1921), Helen Wilkinson Reynolds (1942), even Henry Noble MacCracken (1938), a former president of Vassar College - but the world did not listen. The Clement Moore camp simply brushed them off like Dutchess County deer ticks. What difference could be made by one inexplicably cheerful woman from Massachusetts? Mary, not I, was doing all of the hard work for this investigation, gathering documents, checking facts. Here at Clinton House she would be inspecting old newspapers, Livingston correspondence, estate records, back issues of the Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook. Excusing myself, I removed my white cloth gloves and left her to her research, returning at one that afternoon to pick her up and to take her to Poughkeepsie's Adriance Memorial Library, Department of Special Collections. Then it was on to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park. Before leaving town, Mary deposited two neatly organized piles of documents in my Vassar office - writings "certainly" by Henry Livingston and writings "maybe" by Henry Livingston. A third pile, by far the largest, contained writings "about" Henry Livingston - machine photocopies of newspaper and magazine articles discussing the authorship controversy, plus biographical and genealogical notes, correspondence, account books, and other Livingston family papers.

THE CHALLENGER: HENRY LIVINGSTON JR.

But now comes blithe Christmas, while just in his rear I boned up on Major Livingston's biography. Born in Poughkeepsie on October 13, 1748, Henry was the eldest son of Dr. Henry Gilbert Livingston, a Scotsman, and Sarah Conklin Livingston, a Dutchwoman, or, as we say in Dutchess County, a Dutchess. His paternal grandmother was a Dutchess as well. Everyone on his mother's side was Dutch. But his father's father was a Scot. Henry considered himself a son of Scotland. (Remember that: I'm not slipping in these little facts for nothing.) The first recorded mention of Henry Livingston after his Poughkeepsie christening comes during his early adulthood, when he was a member of and frequent visitor to the Social Club of New York, a place run by God-Save-the-King Tories. When war broke out with the Motherland, Henry and his Yankee Doodle brother were blacklisted from the Social Club. For official business, the eldest son of Henry Gilbert Livingston, Esq., signed himself "Henry Livingston, Jr." dropping the "Jr." after his father's death in 1799. About town, in recognition of his service in the War of Independence, he was called "Major Henry"; and in his old age, while serving as a softhearted Commissioner of Bankrupcy Court, "Judge Livingston." But to family and friends and neighbors, he was always plain Harry, the jolliest man in Dutchess County.Henry's first recorded words are "Happy Christmas," in a love letter dated December 30, 1773, addressed to a creature for whom his heart was stirring, twenty-one-year-old Sarah ("Sally") Welles of Stamford, Connecticut.

A happy Christmas to my dear Sally Welles! The letter ends:

Remember me, my dear Love, to my friends and relations in Sta[m]ford; and remember, my Love, that of all your friends, none loves you as sincerely as your Henry Livingston Henry and Sally were married in Stamford, Connecticut, by Sally's father, the Rev. Noah Welles, on May 18, 1774. The couple set up housekeeping at Locust Grove, a mile south of the village of Poughkeepsie, in a house built by Henry's Scottish grandfather. A surveyer and mapmaker by training, Henry also cut and sold lumber from a sawmill on his property, farmed his land, and operated a landing for sloops called Harry's Point, down on the river. By avocation a journalist and illustrator, Henry contributed engravings, poems , and prose satires to Poughkeepsie newspapers and New York City magazines, adopting such quirky pseudonyms as "Seignior Whimsicallo Pomposo," "Wizard," "Professor Zeritef Sharslow," "Henry Hotspur," and "Peter Pumpkineater." When rising tensions with Britain led to war, there was no question concerning enlistment. Henry's father-in-law had been a pulpit-thumping firebrand for independence, and Henry was himself an American patriot, a New York gentleman of Scots and Dutch descend whose loyalties were to the Federation, not to England. One day Henry opened his music book to "God Save the King" - on page 182 - dipped his quill, lined out "King," wrote in the word "Congress," and rode into the village to join the American Revolution. The Livingstons' first child, Catherine, was born on August 18, 1775 on the eve of Major Henry's departure to fight the British. Next morning Henry wrote to his commander, Colonel Clinton, that was now ready to march:

Dear Sir While serving under Colonel Clinton, and General Montgomery, Livingston kept a journal, still extant, providing an account of his military tour - the highlights of which, for Henry, was an elegant dinner that he organized at Mr. Killip's Tavern in the village of Lapraire, Quebec, his guests of honor being its chiefs and twenty others of the Caghnawaga nation. Also invited was the village priest, "a fat Jolly thing of a Curate who did all the preaching and praying." Henry played the host and master of ceremonies, his introductory speech being translated by "a one-ey'd Chief who understood English very well - & they answered me with all that deliberation, Firmness & serriousness [sic] peculiar to the Indians." Henry adds: "I took especial care that each one had a full plate continually - Soup - Beef - Turkey - Beans - Potatoes - no matter how heterogeneous the mixture, it was equal to them, & all went down." The guests became somewhat less firm and deliberate in their speech after eighteen bottles of clarket, and a good time was had by all. The great tragedy of Henry's early adulthood was the death of his wife in 1783. It took a while for the Livingston household, and Henry's verse, to recover the livliness that was there before Sally's death, but the Major and his children worked at it, observing the celebration of Saint Nicholas Day, Christmas, and New Year's as it had been before. Henry describes the typical Livingston family holiday during these years:

Such gadding - such ambling - such jaunting about To tea with Miss Nancy - to sweet Willy's rout, New parties at coffee - then parties at wine, Next day all the world with the Major must dine! Then bounce all hands to Fishkill must go in a clutter To guzzle bohea and destroy bread & butter... Relatives and guests came from far and near to join in the festivities. Henry and the children sang and played their instruments. There were noisy dinners, wild sleigh rides, knockabout games of Hide and Seek and Keys and the Cushion, with music and dancing till midnight. On September 1, 1793, ten years to the day after Sally's death, Henry Livingston remarried, taking to wife Jane Patterson, by whom he would have eight children. As the kids grew up, they became scattered by marriage and by the opportunity for cheaper land out west, in Ohio, Illinois, and Wisconsin. The Major, who remained in Poughkeepsie, died in his eightieth year, on February 29, 1828, much lamented by family and friends. His surviving sons and daughters never tired of telling stories to their children, and to their children's children, of wonderful Papa Livingston, of his "fine poetical taste," his "great taste for drawing and painting," and his "Night Before Christmas." Perhaps the tales grew some with the retelling and the passing of years. Writing to a niece in 1879, Henry and Jane's eldest daughter, Eliza, recalled how her father would "entertain us on winter evenings by getting down the paint-box, we seated around the table. First he would portray something very pathetic, which would make us to tears. The next thing would be so comic that we would be almost wild with laughter. And this dear, good man was your great-great-grandfather. In one of the Major's extant drawings, a young lady flies in holy dread from a watercolor bugaboo - a monster having the head of a fire-breathing devil, the feet of a monster, and a torso made of a large poultry thigh. Much of the Major's poetry was written for children and never gathered or published. One compassionate lyric from the 1780s is addressed "To my niece, Sally Livingston, on the death of a little serenading wren she admired"; another, to a young second cousin, Timmy Dwight, a boy as "Blythe as Oberon the fairy." Harry urges the lad to party hard on his birthday, to fill his "cormorantal belly" with hasty-puddings and "charming jelly." Fun stuff, fun poetry. You can't read Major Henry Livingston Jr. and not love the man from the top of his jolly head to the tips of his Poughkeepsie feet. His correspondence and published poems and articles are usually witty, sometimes hilarious, never sarcastic; full of love for humanity and driven by an irrepressible joie de vivre - or to say it more properly in Dutch, levenslust.

The world, as represented in Professor Moore's Poems, is a place inhabited by loud children, frivolous maids, scolding wives, loud children, lazy mechanics, loud children, soft-spoken rogues, rude barflies, lewd coquettes and prostitutes, rich men ill-clad, loud children, dull schoolmen, manly-treading female would-be-scholars, and loud children - all of whom must be scolded: the little ones, with patience, and the adults, who ought to know better, with sneering sarcasm.

It would be hard to find two sons of the American Revolution more different from each other than Professor Clement Clarke Moore of Chelsea House, Manhattan, and Major Henry Livingston of Locust Grove, Poughkeepsie. There is no topic about which the two men can be found to agree, from women to music to politics. Moore opposed most democratic reforms, including the movement for free public schools; Livingston argued that children should have equality opportunity, regardless of their gender or complexion or cultural heritage. A foe to women's education, Moore protected his daughters from the harmful effects of book learning, and speaks of learned women with scathing derision; Livingston, while traveling through Canada in 1775, praised the women's zeal for education while critizing the illiteracy of the Canadian men. Moore expresses disdain for the American "savages" and condemns their mode of communication as innately deceitful; Livingston was a friend of the Indians, writes of the aboriginal peoples with admiration, and praises the seriousness and courtesy of their speech. Moore unrepetantly defends human slavery as an institution ordained by god for the health and prosperity of American society - in fact, he owned slaves himself, as many as were convenient to keep the Moore household running smoothly; Livingston in his published journalism as early as 1788 calls for emanicipation, and writes in his private journal that "A land of slaves will ever be a land of Poverty, Ignorance, & Idleness!" The son of a British loyalist during the War for Independence, Moore as an adult denounced thomas Jefferson as a subverter of public morals and a danger to the Commonwealth; Livingston was a die-hard Whig whose lifelong theme, in verse and prose, is that "Love, and all its delectable concomitants" can thrive only "where equality is found or understood." The personal dispositions of Livingston and Moore were as different as their systems of belief. Major Henry celebrates theater, music, and dancing, which combine "to drive far off care and annihilate time / And chase sour sadness away." Moore writes that the man who dances is "like a squirrel cag'd, who, though he bound, / And whirl about his wheel, yet ne'er advances." Women dancers are said to resemble female scholars and prostitutes: "No laws they heed but those which rule the dance." Santa's pipe - removed from the poem by some recent editors under pressure from the anti-tobacco lobby - is unmistably Dutch: "The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth, / And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath." As early as 1748, Tobias Smollett writes of a Dutch sailor taking "a whiff of tobacco from the stump of a pipe." Henry Livingston's imagination is similarly populated by Dutchmen who "puff away care" with a "pipe of Virginia" while Clement Moore likens the lure of tobacco ("Virginia's weed," he calls it) to "opium's treach'rous aid."

Or take the simple word all -- which can be used either as a pronoun, to mean every person or every thing ("All of the children were snug") or as an adverb, to mean totally ("The child was all snug"). Most writers use all as a pronoun more often than as an adverb, but the "Christmas" poet does not. In the poem's first line, it's "all through the house" (not throughout). In line 5 he writes, "all snug in their beds" (not snugly or so snug). These examples are followed in turn by "dressed all in fur" and "all tarnished." that's a lot of adverbial "all" for one short poem. Against those four adverbs are five pronouns: "dash away all," "fill'd all the stockings," "all flew," "Happy Christmas to all and to all a good night." Vintage Henry: in Livingston's early verse, and in Livingston's late verse, and in his verse in between, the pronouns and adverbs are about evenly divided. In Moore's poetry, the pronouns outnumber the adverbs 10 to 1 (and in Moore's prose, by more than 100 to 1). Henry writes "all along," "all blithe," "all blue," "all craggy," "all defenseless," "all delightful," "all early," "all flaming," "all forlorn," "all-hid," "all keen," all this or that, all through the alphabet. It's worth tracing the history of this quaint phrase, "all snug" -- which is common today as "Tuck me in!" but less familiar in the days of Livingston and Moore. By writing "all snug," the author of "The Night Before Christmas" was using an idiom more common in Scotland and Ireland than in England or America. Turning to the Oxford English Dictionary, one learns that "all snug" or "right snug" at first meant all tiday, the earliest recorded instance of which is in 1725, in Allan Ramsay's Gentle Shepherd: "He kames his hair, indeed, and gaes right snug." Great Scot! Allan Ramsay was one of Henry Livingston's favorite poets. The Major even performed Ramsay's poems, set to music, on his flute and violin. The Oxford English Dictionary reports that "snug" later came to mean not only tidy (as in Ramsay) but cozy or comfortable. As the earliest instance of "snug" for cozy, the OED cites Christopher Anstey, The New Bath Guide (1766), a poem already identified as a major influence on both Henry Livingston and on the author of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" (see OED, "snug," ad. 1, ad. 2). For additional examples, I turned to Literature Online -- an archive described by the publisher as a "fully searchable library of more than 260,000 works of english and American poetry, drama, and prose" -- and found that the second earliest instance of "all snug" appears in John O'Keeffe's libretto The Highland Reel (1789). That's of interest as well: the two latest items in Henry Livingston's music book (1776-1784) are from John O'Keeffe (Amo Amas," and "Can I declare" [1784], p.52). Henry Livingston and the author of "The Night Before Christmas" display remarkably similar reading habits.

Henry Livingston is not the only poet who might have written "all snug." In 1801, Matthew Lewis published in his

Of all the poems and letters and magazine articles that Henry Livingston wrote during his eighty years on the planet,

the earliest to survive begins with the greeting "A happy Christmas to my dear Sally Welles." "A Visit from St. Nicholas"

ends with the greeting "Happy Christmas to all." One might guess that a "happy" Christmas, which today sounds quite ordinary,

was as commonplace in Livingston's time as a "merry" Christmas, but the guess would be wrong. Literature Online, for example,

locates the earliest "Happy Christmas" in 1823 in a little poem beginning "'Twas the night before Christmas..." A broader

survey of English and American literature, from 1390 ("murie Cristes masse") through the Christmas of 1823, shows that "Merry

Christmas" was commonplace and "Happy Christmas" rare. Charles Fenno Hoffman, who ascribed the poem to Moore, changed "Christmas"

to "New Year" at lines 1 and 56. Other editors changed the last line of "A Visit" to read "Merry Christmas to all..." Many later editors

followed suit, as if "Happy Christmas" were a mistake. But a "Happy Christmas!" sounded just fine to Henry Livingston.

Whether Clement Moore preferred a "Merry Christmas" or a "Happy Christmas" cannot be determined. From what I've seen of

his extant writing in verse and prose, including personal correspondence, Moore never said "Happy Christmas" (or "Merry Christmas")

to anyone.

"The Night Before Christmas" is as different from Moore's other children's verse as Christmas cookies from steamed spinach.

The 1844 Poems includes three other poems (besides "Christmas") addressed to Moore's children. In one, he urges his little

ones to look on his portrait and remember him after he lies mould'ring in the tomb. In the second, he urges the children to look on the

freshly fallen snow and remember that they, too, and their transient joys, must perish from the earth. In "The Pig and the Rooster,"

written about 1833, Moore allegorizes a "conceited young rooster" and a "lazy young pig" (a fashion-monger and a wine-bibbing glutton),

and a "counselor owl" (who despises them both). Moore's supporters always point to the form of this anapestic "Pig and Rooster"

fable as evidence that the Professor really was capable of writing a children's poem like "A Visit from St. Nicholas,"

Major Livingston's heirs point to the content as evidence that he couldn't have. Major Livingston's heirs are right.

Clement Clarke Moore reports that "The Night Before Christmas" was written in 1822, and there may yet be nine reasons to believe him,

to wit; his mode of entry - coming down through the chimney - and eight reindeer: Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donder, and Blitzen.

At least two of Major Henry's children said that their father wrote "The Night Before Christmas" in 1808, yet it has appeared to past researchers

that "A Visit from St. Nicholas" cannot be that early. In 1813, Samuel Wood published False Stories Corrected, in which a teenaged pelemicist

warned New York parents not to share with children the "improper idea" that "Old Santaclaw has come down Chimney in the night" to fill their

stockings. This is the first recorded reference to Santa as an elf-sized saint who comes down with a bound through the chimney. And doesn't that

prove that False Stories Corrected came before "A Visit from St. Nicholas"?

Eight years later, William Gilley, another New York bookseller and a friend of Clement Moore's, published A New Year's Present to the Little Ones

(third in a series of booklets called "The Children's Friend"). Gilley's 1821 paperback contains just one poem, a didactic parable beginning "Old Santeclaus with much delight /

His reindeer drives this frosty night..." The first of eight color engravings is a sketch of old Santeclaus on a city rooftop covered with snow.

In the background is a cathedral spire. Santa sits in a sleigh pulled by a leaping reindeer. Everything else in A New Year's Present to the Little Ones

can be found in the earlier literature, but the reindeer was new, entirely original, quirky, and quintessentially American, a newly coined myth for a society

where ancient national traditions were all jumbled together, as in "A Visit from St. Nicholas" with its mishmash of fairy lore, religious tradition, and Norse mythology.

In academic and journalistic accounts of Santa's reindeer it has been a commonplace to observe that Moore (or whoever) borrowed the reindeer idea from Gilley's

1821 children's book. (As Santa's historian, Charles Jones, has said, "Moore knew how to multiply; he was perfectly capable of turning one deer into eight...)

It's not so easy as that. Moore could multiply one reindeer into eight, but from whom did the dull wit who wrote Gilley's "Old Santeclaus" poem acquire the original reindeer

in 1821? Probably from Henry Livingston.

The sky, in Major Henry's imagination is a busy place. As in "A Visit," where reindeer like dry leaves "mount to the sky," Livingston writes of children and souls and

storms and even lambkins who mount "to the sky,"

or "to the skies," [also to the skies] or "to the bright empire of the sky";

of Oberon, King of the Fairies, whose carriage is a nutshell pulled by a team of katydids; of a handsome white-stocking'd colt who "moves

as if he danced on air."

In Major Henry's verse and prose, whales gambol above the waves, boats fly, angels hover,

kittens bound, gnats flit, dancers float.

Even his dinosaurs can mount to the sky. When the

bones of a "gigantic quadruped" were discovered in Ulster County's Little Britain in 1783, the locals were awestruck by the majesty of the dinosaur.

In a short story for the New York Magazine two hundred years before Jurassic Park, Livingston imagines one of these ancient monsters hiding out

in the American wilderness, devouring men, flattening villages, ascending to the bluest summit, and leaping over the waves of the west at a bound.

Major Henry's interests extended beyond paleontology and aeronautics. As Dutchess County's local expert on the Arctic, Livingston wrote of northern cultures

around the world, from Labrador to Norway

to Russia to Siberia, borrowing everywhere from books that provide accounts of Scandinavian elves, Lapland reindeers, and of

the Norse god, Thor, whose chariot was said to have been pulled by airborne "He-Goats". By combining the pipe-smoking Dutchmen of

the Hudson Valley with the reindeer of Lapland and the flying goats of Norwegian mythology, our Christmas poet created an American original. Santa has traveled by

reindeer-drawn sleigh ever since.

But there's another oddity about the reindeer: Whenever a jolly Dutch burgher and his Dutchess were startled or angry or delighted, the oath, "Dunder and Blixem!"

would escape their lips ("Thunder and lightning!") - not "Donder and Blitzen." Dutch fondness for this ancient oath was proverbial - but in English and American

literary texts earlier than 1836, it's always "Blixem" (or "Blixim" or "Blixum", in modern Dutch, Bliksem). The only recorded instance of

"Blitzen" earlier than 1836 is in Sir Walter Scott's novel, Guy Mannering, first published in America in 1815: Sir Walter, who was no Dutchman,

has eight instances of the German "Blitzen!" - each mistaken instance being placed in the mouths of dunderheaded Dutchmen. But Henry Livingston, who was three-quarters

New York Dutch and a resident of the Hudson Valley, could not have made such a mistake.

I asked Mary Van Deusen, on whose indefatigable research skills I still depended, to find me a photofacsimile of the 1823 test of "A Visit from St. Nicholas." I had

a hunch that the text did not say "Donder and Blitzen." If it did, we had a problem. Mary was able in a few days time to locate a copy of the original Troy Sentinel text,

which she sent me in facsimile, via the Internet.

Dunder and Blixem! Orville Holley, editor of the Troy Sentinel, got it right.

Holley also got something else right that was thought by later editors to be wrong:

the 1823 Sentinel text has odd, offbeat punctuation of Santa's giddyap

to the reindeer: "Now! Dasher, now! Dancer, now! Prancer, and Vixen, / On! Comet, on!" (etc).

Early editors weren't sure what to do with that.

Mr. Holley left it alone.

The next several editors followed Holley's lead, but successors tinkered with the exclamation points, trying to fix the rhythm; and Holley himself, when he reprinted

"A Visit" in 1829, amended the original printed text to read, "Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now, Prancer!

now Vixen! / On, Comet! on, Cupid! on," (etc.) When Clement Moore reprinted "A Visit" in his 1844 Poems, he used the

standardized punctuation. Modern editors have followed suit, blaming the misplaced exclamation points on Miss Harriet Butler, whom legend credits as the source for

the 1823 Sentinel text.

Interestingly, Henry Livingston had the same odd practice of peppering his verse with offbeat exclamation marks that interrupt the

da-da-DUM meter: "And happy - thrice happy! Too happy! the swain / Who can replace the pin or bandana again..." Even in his prose

Henry puts exclamation points where you don't quite expect them. Writing as a young man, he writes of human existence that

"our business is Praise! & Love!

the unremitting theme" (1784). Forty years later, aged seventy-eight, he still registers that old exuberance: "Dear, Dearest! son!..." (1825). Miss Harriet Butler should

not be blamed for punctuation of the original 1823 Troy Sentinel text.

Early reprints of "A Visit" follow the Sentinel's text verbatim. The first major interventions were made by Charles Fenno Hoffman, who in 1837 ascribed the poem to

Clement Clarke mOORE. Hoffman changed "Blixem" to "Blixen" for a perfect rhyme, and "Dunder" to "Donder," and tinkered with the exclamation points. When Hoffman's text

was reprinted in The Rover, the hapless printer introduced still another little change - "Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now, Prancer! now, Nixen!..." "Nixen" was a

printer's error. But the change from "Blixem" to "Blixen" was a deliberate sophistication by which Hoffman fixed an off-rhyme but corrupted the original

author's perfectly correct Dutch.

To the eyes of Clement Clarke Moore, who knew German but not Dutch, neither "Blixem" nor "Blixen" looked right. Reprinting "A Visit from St. Nicholas"

with his 1844 Poems,

Moore called the eighth reindeer "Blitzen":

In 1856, again in 1862, Professor Moore copied out the text of "A Visit from St. Nicholas," signed it, and distributed these autographed copies as gifts (one of which

recently sold at a Christie's auction for $255,000). One of the Professor's biographers, Samuel Patterson, describes these autographied copies of 1856 and 1862 as

"irrefragable proof that Clement Clarke Moore composed the poem," but in fact these autographed manuscripts indicate that Clement Clarke Moore did not know the original

names of his own Dutch reindeer. In the manuscript copies, as in the printed Poems, Moore makes the same telltale mistake, writing "Donder and Blitzen," not suspecting

that Saint Nick is a Dutchman who says "Dunder!" and "Blixem!" Moore's corrupt "Blitzen" is one more indication that he stole "Christmas" - Santa Claus, sleigh, reindeer, and all -

from a portly rubicund Dutchman named Henry Livingston.

When the evidence is laid out on the table, one cannot help but wonder how "A Visit from St. Nicholas" ever came to be associated with an old curmudgeon like

Clement Clarke Moore in the first place.

One well-kept secret - unknown, evidently, even to the Professor's many biographers - is that Clement Moore as a young

bechelor published many of his poems under the pseudonym "L." In 1844, when publishing his collected Poems under

his own name, not under his youthful pseudonym, the Professor must have been disappointed in the response: reviews of his

Poems ranged from sarcasm to tepid praise. But one reviewer, writing for The Churchman, the magazine

of the Protestant Episcopal Church of America, gave Clement Moore's Poems a ringing endorsement, a review suitable

for framing. I don't know for sure who wrote it, but the author of that flattering Churchman blurb signs himself "L."

Perhaps the old Professor wasn't humorless after all. Perhaps he even wrote his own book review.

On January 16, the Poughkeepsie Journal published a corrupt text of "A Visit from St. Nicholas or Santa Claus," ascribed to no one;

and on February 29, Henry slipped away. He was buried by the wife and children and friends he loved, beneath a grove of locust

trees he loved, beside the river he loved. An obituary in the Journal, unsigned, describes him as "a great lover of the fine

arts, and particularly fond of poetry and painting. His best qualities, however, shone in the domestic circle, over which his tender

feelings, his warm affections, and his sprightly and instructive conversation shed uncommon interest and lovliness." Sixteen

years later, a wealthy stranger, a scholar named Clement Clarke Moore, would lay claim to "A Visit from St. Nicholas."

No matter. Henry Livingston gave to his children, and neighbors and friends and readers, much that could not be taken away.

Compared to such an extraordinary life, "A Visit from St. Nicholas" is indeed a "trifle," just as Dr. Clement Clarke Moore had

said it was. Henry Livingston was the spirit of Christmas itself.

|

![]() Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises

Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises