I didn't start out planning to add myself to the list of searchers. It was actually sort of

accidental that I stumbled over Henry. What I was trying to do was discover something about

my father. Father had been a Major in the army.

And a poet in Greenwich Village.

He was also, unfortunately, an alcoholic, a problem not so uncommon in the New York City

of the 1930's.

Mother had left

father when I was just six weeks old, and tried to leave all trace of him behind, as well.

But when he died at the early age of 49, she couldn't avoid the box of photographs that came, and so

she packed them away in her files. I found them there, as well as a

set of letters he wrote begging her to come back.

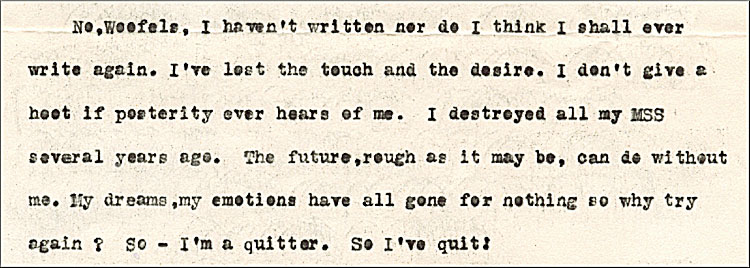

One of them hit hard the daughter trying

desperately to know her dead father.

Father might have given up, but he also said that he trusted me - me, this daughter he'd last seen as a six-week old infant - to help him.

I was determined that I was not going to do without him, and

I figured that the future would just have to take him, too.

But when I tried to find his poetry, I failed. And so the hopes I had built up, that I could

find a virtual way to bring father back, failed as well.

But I don't give up easily, and I kept worrying the problem. I finally decided that another

path to father might be through his family. One of them must have a copy of his poetry

book. Along with the photographs was an obituary for

his mother. That was my starting point.

According to the small scrap of paper, Catharine was the daughter of Henry Burnett and

descended from Henry B. Gibson of Canandaigua NY. She was also carried to her grave

by the governor of Colorado and three generals! I figured I had a chance.

In Canandaigua I had my first genealogical shock. Henry B. Gibson turned out to be one of the richest men

in western New York. He was Gibson Street in Canandaigua, Port Gibson NY,

a canal company (which never built anything), a bank and two railroads, the latter of which

was merged with several others to form the New York Central. I sat down pretty hard.

There was a file on Henry in the Ontario Historical Society that had in it a family tree.

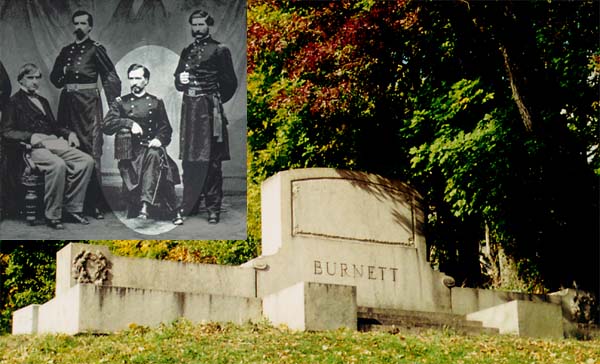

Henry Burnett showed up as a a general. Not too surprising, given

grandmother's pallbearers. It took longer than I expected, though, to find out anything about him

because he wasn't a battlefield general. He was,

second genealogical shock, one of the special judge advocates at the Lincoln Assassination

Trial, that is, one of the prosecutors! I sat down for awhile over that one.

In Goshen New York, where General Burnett lived toward the end of his life, I discovered a 40 page

paper on his memories of the trial. I also found

his grave high up on a

hill overlooking what turned out to be his horse farm. It was a huge monument, built so that

he would be remembered. But the only thing carved into the stone was the surname BURNETT. The

details of who he was were gone, stolen along with the plaque which had been attached to the

stone.

And so great grandfather, like father, was lost to the future.

By now I was adopting ancestors like stray puppies. I hurt for great grandfather disappearing,

and wanted to find some way to bring him back, especially since I had been able to do nothing for father.

I put the General's paper onto the Internet, and I found

a local historian who thought that we could get a grant to have the plaque remade -- if we could find

out what it said. But when I tried to find out, I failed there, too.

So I turned up my collar against the mental rain and went back to butting my head against father's tree,

hoping to shake something loose. Between Henry Gibson and Henry Burnett there was one

another ancestor to examine, Henry Livingston Lansing. Do we begin to note a predominance

of Henrys in my tree?

Up to then I hadn't even known many men of that name, though I had

chosen it as the title of a movie screenplay that was flogged for me in Hollywood by Writers & Artists.

There was, too, the white Bichon draped over my arms as I typed, a pup I had

named Henry in memory of the play. Henry was suddenly getting a lot of company.

Brigadier General Henry L. Lansing turned out to be

the brother of Brigadier General Henry Seymour Lansing.

Now it was just silly. I sighed with relief when Henry and Henry's father

turned out to be Barent Bleecker Lansing, and his grandparents, Arthur Breese and

Catharine Livingston. It was on Catharine that I got stuck. Trying to track down

a Catharine Livingston gets harder when there are twenty-six of them.

There were, in fact, so many of them that I had no idea how to find

out which one was mine. So I did what I tend to do when stuck, I reached out and touched someone.

Bless AT&T. Well, in this case, the Internet. I sent mail to Bob Livingston, a U.S. Representative

in D.C., asking whether he knew of any Livingston family associations. A day later the phone rang

and a deep male voice announced, "Hi, this is Bob Livingston. Welcome to the Livingston family!"

That had to count as genealogical shock number three.

From Bob I got a pointer to the Clermont estate on the Hudson River, and to the Friends of

Clermont. And from them I got Catherine's parents - Henry Livingston, Jr. and Sarah Welles.

(There are only twenty-four Henry Livingstons!)

I also got a very deep respect for a politician who reaches out to people, not for what they can

do for him, but because he genuinely loves people. A rare quality in any politician.

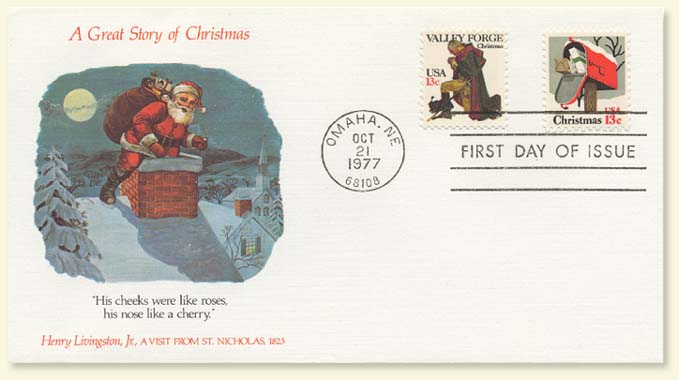

Anyway, back to the dance. Armed with Henry's name, I threw it into a search engine on the Internet.

And that's when I discovered a webpage describing him as the actual author of "A Visit From St. Nicholas."

I'd count this as genealogical shock number four if I had believed it. But I didn't, so I won't.

I did decide to go to Poughkeepsie, though, to learn more about this particular Henry.

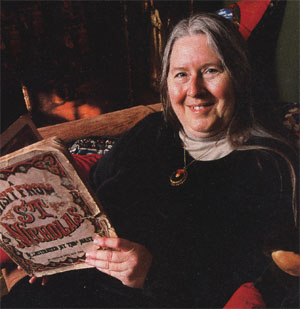

It was at the Dutchess County

Historical Society that I found a transcript of Henry's poetry manuscript book. It was funny

and charming and, in some way, it was compelling. One of the poems, actually a letter to his youngest

brother, Beekman Livingston, sounded amazingly like the Christmas poem. That's when my nose

started twitching. But I was still a Missouri skeptic. I had to be shown. I decided it was

worth the effort to search out Moore's poetry. Little did I realize what effort I was about to get

myself into.

It was three weeks later, and I was in the library at Brown University printing out pages from a microfilm

copy of Moore's 200 page book, Poems. I had found not a single reprint of the book, something

that had surprised me. But now, as I sat watching the pages slowly print out, it all became clear.

The reason there was no reprint because no one would have bought it!

This was terrible poetry. It was

self-absorbed, egotistical, and moralizing. And it was remarkably consistent.

As a writer myself, I believe that who we are shines out of every paragraph we write. Styles can

be changed, pace and pattern can be varied, but psychology usually stays the same. I could feel

Clement Clarke Moore in every word he wrote. And I wouldn't have gone to lunch with him if he'd

begged!

Now Livingston I already knew from his writing. I knew that he wrote frequently in the style of the

Christmas poem. And I had already realized that his points of view were consistent with those of

the Christmas author. That is, he was a kind and good man who could slip easily into the

point of view of a child.

But sitting in front of that microfilm machine, with Moore feeding out page after page, genealogical

shock number four started setting in. Henry Livingston, Jr. really was

the true author of Night Before Christmas.

And if I had thought father and great grandfather had been crying out for my help to be

remembered, this new relative was screaming.

Back To Top