The Most Recent Research

In 2016, Auckland University Emeritus Professor MacDonald P. Jackson published his multi-year research

into the authorship of the famous Christmas poem, "Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas," or as we know it,

"The Night Before Christmas."

Jackson is best known for his work on Shakespeare, with his latest work done as part of the editorial team

that recently published the

"The New Oxford Shakespeare."

Jackson's book, "Who Wrote 'The Night Before Christmas'," uses

statistical analysis to identify the unconscious traits in

linguistic elements of poetry to create tests which can statistically discriminate the poetry of Clement Moore from the poetry of Henry Livingston. Once Jackson had

these tests, he applied them to the Christmas poem. The result of all of the tests was to definitively identify the characteristics of "The Night Before Christmas"

with the poetry of Henry Livingston, not the poetry of Clement Moore.

These tests included the commonly used author attribution tests like frequency of small words, but Jackson also broke important new ground by

analyzing phoneme pairs - the sound of words -

which track how the tongue and lips move while reciting the words aloud.

You can actually look at the original data for Initial Ands!

Two hundred years of misattribution have now been corrected. The true author of "The Night Before Christmas" was Henry Livingston, Jr. of Poughkeepsie, not

Clement Clarke Moore.

The Poem was Written Around 1807

The date is approximate because it relies upon the memories of the four children who were old enough to remember Henry Livingston reciting it,

ink still wet - his sons Charles, Sidney and Edwin, and the neighbor girl who would marry Charles, Eliza Clement Brewer.

After Henry's death in 1828,

the original manuscript, with corrections, was inherited by Sidney, who found it among his father's papers. Sidney passed it on

to his brother Edwin, who moved to Wisconsin and initially lived with his sister Susan and her husband. During one of house fires suffered by

Susan's family, the manuscript burned.

The Poem's First Known Publication

Although he had published extensively after the death of his first wife, Sally Welles, Henry's publications mostly stopped with his second marriage in 1793.

Surviving manuscript pieces, such as Dialogue, that he wrote for his growing second family, were never published.

His major publications of the period were his Carrier Addresses, the New Year poem that was given by the news carrier as a gift to subscribers with the

expectation of getting a tip in return. Henry wrote Carrier Addresses from 1787 to 1823.

But now comes blithe Christmas, while just in his rear,

Advances our saint, jolly, laughing, NEW-YEAR,

Which, time immemorial, to us has been made

The source of our wealth and support of our trade,

[1803 Poughkeepsie Journal Carrier's Address, Adriance Library]

But hark what a clatter! the Jolly bells ringing,

The lads and the lasses so jovially singing,

Tis New-Years they shout and then haul me along

In the midst of their merry-make Juvenile throng;

But I burst from their grasp: unforgetful of duty

To first pay obeisence to wisdom and Beauty,

My conscience and int'rest unite to command it,

And you, my kind PATRONS, deserve & demand it.

On your patience to trespass no longer I dare,

So bowing, I wish you a HAPPY NEW YEAR.

[1819 Poughkeepsie Journal Carrier's Address, Adriance Library]

After Henry's death, son Charles took back to Ohio a Poughkeepsie Journal printing that he delighted in reading to his children and grandchildren as the work of his father.

It was probably this clipping that gave rise to the family stories about an early publication of the poem. Since a version with red-deer

instead of reindeer appeared in January of 1828, three weeks after Christmas, as Henry lay dying, it's possible that this publication was done as a gift to him and was the source of the

family stories.

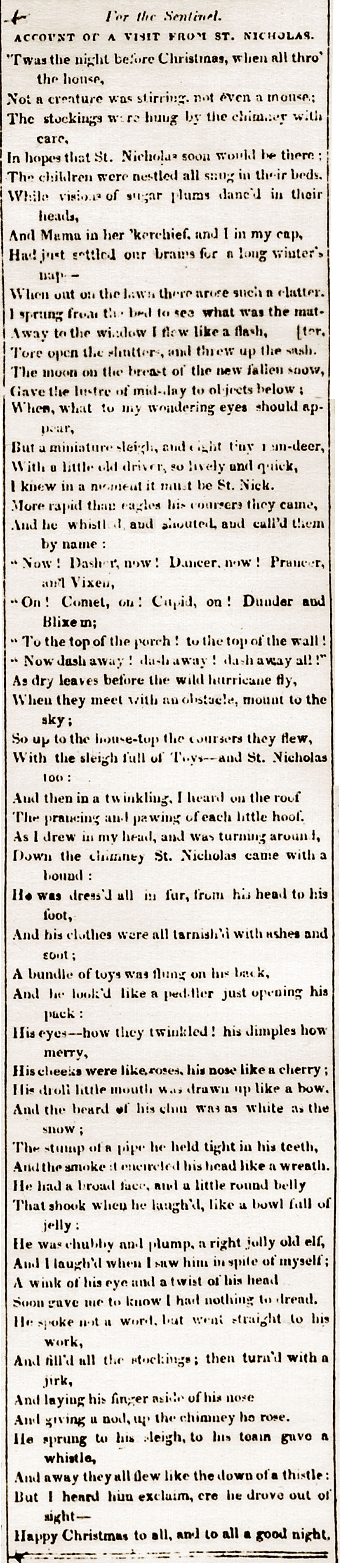

The first known publication of the poem was the one in the Troy Sentinel of 23 Dec 1823.

There is no question that the poem originally came out of the Clement Moore home. For the Livingstons, the question has always been, "How did it get there?"

The Poem Moves from the Livingston Household to the Moore's

Livingson family stories talk of a governess visiting with the Livingstons before

stopping off at the Clement Moore household on her way down south to work. There are no specific names attached to this story, but it is

interesting to look at Henry's next door neighbors, John Moore and his wife, Judith Newcomb Livingston Moore.

Judith was Henry's first cousin, while John's brother was married to Clement Moore's aunt.

Keep in mind that Henry is of Clement Moore's FATHER'S

generation, not Clement Moore's.

John and Judith's daughter, Lydia Hubbard Moore, married Episcopalian minister Rev. William Henry Hart, and lived in Virginia. Her children were old

enough to require a governess in 1823, and her household could have been the destination for the governess who had a copy of the poem.

The Poem Moves from the Moore Household to the Troy Sentinel

There is no question that Clement Moore recited "Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas" to his children as his own work. He also told them not

to let it out of the house. But one of the children allowed Harriet Butler, of Troy NY, to take a copy of the poem. In 1844, Moore received

a letter from Norman Tuttle, the proprietor of the Troy Sentinel identifying the wife of Daniel Sackett as the woman who gave the poem to the paper's editor,

Orville Holley. The likely assumption is that Harriet Butler gave the copy to Mrs. Sackett.

By the way, Harriet Butler's brother, Rev. Clement Moore Butler of Troy New York, married Frances Livingston Hart,

the granddaughter of Henry's next door neighbor and cousin, Judith Moore and her husband John Moore!

Why Did Moore Do It?

Moore was known to write Christmas poems. An anonymous poem was identified by attribution researcher and Vassar Professor Don Foster as being by Moore.

"Another possibility, and a better one, is that Mr. Moore wrote Old Santeclaus. If fact, if Old Santeclaus was not written

by the original Grinch, Professor Clement Clarke Moore himself, then call me "Rudolph" and never let me play in reindeer games. ...

That 1821 Santeclaus poem has the Professor's stylistic fingerprints all over it. Giving credit where credit is due, I think Moore

may be credited with having written one of America's first Santa Claus poems -- not A Visit from St. Nicholas, but Old Santeclaus."

Old Santeclaus

Old SANTECLAUS with much delight

His reindeer drives this frosty night,

O'er chimney-tops, and tracks of snow,

To bring his yearly gifts to you.

The steady friend of virtuous youth,

The friend of duty, and of truth,

Each Christmas eve he joys to come

Where love and peace have made their home.

Through many houses he has been,

And various beds and stockings seen;

Some, white as snow, and neatly mended,

Others, that seemed for pigs intended.

Where e'er I found good girls or boys,

That hated quarrels, strife and noise,

I left an apple, or a tart,

Or wooden gun, or painted cart.

To some I gave a pretty doll,

To some a peg-top, or a ball;

No crackers, cannons, squibs, or rockets,

To blow their eyes up, or their pockets.

No drums to stun their Mother's ear,

Nor swords to make their sisters fear;

But pretty books to store their mind

With knowledge of each various kind.

But where I found the children naughty,

In manners rude, in temper haughty,

Thankless to parents, liars, swearers,

Boxers, or cheats, or base tale-bearers,

I left a long, black, birchen rod,

Such as the dread command of God

Directs a Parent's hand to use

When virtue's path his sons refuse.

[From New-Year's Present to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve. 1821.]

A handwritten manuscript of Moore's gives another Christmas poem from the same period.

From St. Nicholas

What! My sweet little Sis, in bed all alone;

No light in your room! And your nursy too gone!

And you, like a good child, are quietly lying,

While some naughty ones would be fretting or crying?

Well, for this you must have something pretty, my dear;

And, I hope, will deserve a reward too next year.

But, speaking of crying, I'm sorry to say

Your screeches and screams, so loud ev'ry day,

Were near driving me and my goodies away.

Good children I always give good things in plenty;

How sad to have left your stocking quite empty:

But you are beginning so nicely to spell,

And, in going to bed, behave always so well,

That, although I too oft see the tear in your eye,

I cannot resolve to pass you quite by.

I hope, when I come here again the next year,

I shall not see even the sign of a tear.

And then, if you get back your sweet pleasant looks,

And do as you're bid, I will leave you some books,

Some toys, or perhaps what you still may like better,

And then too may write you a prettier letter.

At present, my dear, I must bid you good bye;

Now, do as you're bid; and, remember, don't cry.

[Museum of the City of New York, Doc #54.331.4.

"Little Sis" was daughter Charity Elizabeth Moore, born 1816.]

It's possible that Moore had no Christmas poem written and took advantage of the copy

left by the governess. Since he had, according to William Smith Pelletreau's 1897 biography,

told the children not to let the poem out of the house, he might have felt it was

safe to read the wonderful verses to the children he dearly loved. After all, who would ever know.

Moore Waited 21 Years To Take Credit

Once the poem acquired its fame, Moore was stuck. His children believed the poem to be his.

He'd said it was. And any day the real poet might step up and claim it. Moore was the only child

of the Episcopal bishop of New York City. How did you tell your children, "Sorry, Father was just kidding."

You don't.

But the family knew and, through them, Moore's friends knew. In 1837, one of those friends,

Charles Fenno Hoffman, published the poem under Moore's name in his book, The New-York Book of Poetry.

Still no whisper from the real poet. Henry, by then, had been dead for nine years.

In 1844, encouraged by his children, Moore wanted to publish his poetry. His children wanted him to

include the Christmas poem. Though Moore considered it trivial, even if famous, he was still nervous

about putting it under his own name. So he wrote to the owner of the Troy Sentinel, who responded

in a letter that he wrote on the back of an 1830 Troy Sentinel broadsheet of the poem.

Yours of 23rd inst making enquiries concerning the publication of "A Visit from St Nicholas" is just received.

The piece was first published in the Troy Sentinel December 23rd 1823, with an introductory notice by the Editor,

Orville L. Holley Esq: and again two or three years after that.

At the time of its first publication I did not know who the author was, but have since been informed that

you were the author. I understand from Mr. Holley that he received it from Mrs Sackett, the wife of

Mr Daniel Sackett who was then a merchant of this City. It was twice published in the Troy Sentinel,

and being much admired and sought after by the younger class, I procured the engraving which you will

find on the other side of this sheet and have published several editions of it.

The Sentinel has for several years been numbered with the things that were: and Mr Holley, I understand, is now in Albany editing the Albany Daily Advertiser. I was myself the proprietor of the Sentinel.

[N. Tuttle to Clement Moore, 26 Feb 1844, Museum of the City of New York]

Moore then published the poem in his own book, Poems.

But There Was a Problem

The problem didn't show up until seventy-six years later, when a great grandson of Henry's,

William Sturgis Thomas, made the Livingston claim to the poem public. Moore's grandson

panicked and obtained a deposition from a cousin who had heard her father's retelling of

what Moore had told him. In that desposition, Maria Jephson O'Conor explained:

Clement C. Moore married Catherine Eliza Taylor, sister of my grandfather Elliot Taylor. My late father, Colonel Henry V.A. Post, married Maria Farquahar Taylor, daughter of my said grandfather.

Under these circumstances my father became very well acquainted with Mr Moore. My father told me Mr Moore himself related to him the following circumstances under which he came to write the poem entitled "A Visit from St. Nicholas."

It was Christmas Eve and Mrs. Moore was packing baskets of provisions to be sent to various people in the neighborhood, as was her custom. She found one turkey was lacking and so told her husband. Though late, he said he would try to get one from the market.

On his return from the market he was struck by the beauty of the moonlight on the snow and the brightness of the star lit sky. This, together with the thoughts of the holiday season, suggested to him the idea of writing a few lines in honor of St Nicholas. He told my father he immediately went to his study and wrote the poem.

Mr Moore also told my father when he came to publish the same, with some of his other poems,

he only made two slight changes in the lines as originally written by him.

Maria Jephson O'Conor

The above Mrs. John C. O'Conor (nee Post) read and signed the above statement in my presence the 23rd day of December 1920

Casimir de R. Moore

[Deposition of Maria O'Conor to Casimir de Rham Moore, 23 Dec 1920,

Museum of the City of New York]

The problem was that there were indeed a few small changes noted on the poem printed on the back of Tuttle's letter. And these

corresponded with the differences between that printing and Moore's published version. So Moore obviously thought what he

held in his hands was the original version of the poem.

It wasn't.

It was the 1830 version of the poem which Orville Holley had extensively edited.

Moore didn't know the difference between that version and the original version of "his" poem.

For more details, read about the possible Smoking Gun.