|

|

| Historical Articles | Chronological Articles |

|

Historical Arguments for Henry Livingston, Jr. as the Author of "Night Before Christmas" |

|

|

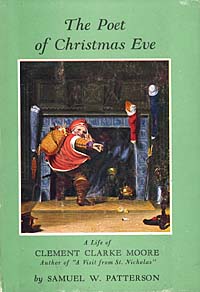

"The Night Before Christmas," actually titled "An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas," was first published anonymously in the Troy (New York) Sentinel on December 23, 1823, and was prefaced with a note by the editor, Orville L. Holley, setting the scene: We know not to whom we are indebted for the following description of that unwearied patron of children -- that homely, but delightful personification of parental kindness: -- Sante Claus, his costume and his equipage, as he goes about visiting the fire-sides of this happy land, laden with Christmas bounties; but, from whomsoever it may have come, we give thanks for it. There is, to our apprehension, a spirit of cordial goodness in it, a playfulness of fancy, and a benevolent alacrity to enter into the feelings and promote the simple pleasures of children, which are altogether charming. We hope our little patrons, both lads and lasses, will accept it as proof of our unfeigned good will toward them -- as a token of our warmest wish that they may have many a merry Christmas; that they may long retain their beautiful relish for those unbought, homebred joys, which derive their flavor from filial piety and fraternal love, and which they may be assured are the least alloyed that time can furnish them; and that they may never part with that simplicity of character, which is their own fairest ornament, and for the sake of which they have been pronounced, by authority which none can gainsay, the types of such as shall inherit the kingdom of heaven. Clement Clarke Moore, born in 1779 son of the clergyman who gave communion to Alexander Hamilton as he lay dying after his duel with Aaron Burr, is now consistently credited as author. Moore, a professor "of Biblical learning and interpretation of Scripture" in New York City, may not deserve the honor. The chances are excellent it should go to a sometime major in the Revolution, land surveyor and "renaissance man" from Dutchess County, Henry Livingston, jr. (1748-1828). Most people who have taken time to look into the scholarly enigma agree that Harriet Butler, the eldest daughter of a Troy clergyman, heard Dr. Moore read the poem in his home, probably before Christmas Day in 1822, was sufficiently entranced to copy it down in her album and to give it to Holley for publication the following fall. The mystery lies in where Dr. Moore got the verse he read. "An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas" was not publicly claimed by Moore until 1844 when he included it in a volume of thirty seven poems, prefacing the collection with the statement that all but two, attributed to his wife, were "written by me." Twenty-one have subtitles telling why he wrote them: nine, including "The Night Before Christmas" have no subtitles at all. And while one doesn't like to question the veracity of a professor of "Scriptural interpretation," the anthology itself clearly indicates that Moore was not in fact the author of at least fivce of the thirty-five verses he claimed, two being assinged by their own subtitles to William Bard and P. Hone and three being direct translations of Italian and Greek works. What the good professor meant by "written by me" is moot. Perhaps, in the fashion of country singers, he felt anything he revised or touched up could be classified as his. Or perhaps he felt that works he ahd read, and so interpreted, and called "favorites" were written by him in some sentimental way. When he was eithty-three years old and one year away from death, he was interviewed as to the authorship of the poem. Then he said that "a porty rubicund Dutchman, living in the neighborhood of his father's country seat, Chelsea, suggested to him the idea of making St. Nicholas the hero of the Christmas piece," and that Miss Butler had not received her copy of the poem from him, but rather from a transcript made by one of his remale relatives." He also remarked that he had written the poem forty years before for his "two children." However the fact that Dr. Moore had three children in 1822 makes the whole pattern of his recollection suspect. To be sure, Livingston's descendants were (and are) convinced that Moore did not compose the poem and that "what really happened" is recorded in an old letter from Elizabeth Livingston Montgomery, though the scholarly detectives finds it delicate to explain why Moore, who was unmarried and perhaps twenty-five years old, should be employing a governess for "his children." The little incident connected with the first reading of "A Visit from St. Nicholas" was related to me by my grandmother, Catherine Breese, the eldest daughter of Henry Livingston. As I recollect her story there was a young lady spending the Christmas holidays with the family at Locust Grove. On Christmas morning Mr. Livingston came into the dining-room, where the famlly and their guests were just sitting down to breakfast. He held the manuscript in his hand and said that it was a Christmas poem he had written for them. He then sat down at the table and read aloud to them "A Visit from St. Nicholas". Al l were delighted with the verses and the guest, in particular, was so much impressed by them that she begged Mr. Livingston to let her have a copy of the poem. He consented and made a copy in his own hand, which he gave to her. On leaving Locust Grove, when her visit came to an end, this young lady went directly to the home of Clement C. Moore, where she filled the position of governess to his children.The truth probably is that Moore heard verses about a visit from St. Nicholas somehow, somewhere, perhaps from the "Dutch gardener," perhaps in his twenties from a governess or guest. He probably reworked these verses, possibly adding enough that he came to think of them as his own. Probably the original from which he worked and which had come to him via the gardener or "young lady" was a poem by Henry Livingston, Jr. Certainly, Livingston makes a better father for this particular brainchild than Moore. Moore was a learned, ponderous man, "educated for the church," with a limited penchant for gaiety, while Livingston was a whimsical chap who once switched the lyrics in his music book from "God Save the King" to "God Save Congress" and who produced a steady stream of light, occasional verse, much of it in the same meter as "The Night Before ..." To my dear brother Beekman I sit down to write Legends attributing "An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas" to "their Henry" abound in the Livingston family. They tell how the poem was "first read to the children at the old homestead before Poughkeepsie" in about 1804 or 1805; how long aho "my brother, in looking over his papers, found the original"; how the treasured manuscript was destroyed in a Wisconsin fire in 1847 or 1848; how astonished everyone was when the poem was attributed to Dr. Moore; and how, in the 1860's, when one of the men in the family was teaching at Churchill's Academy at Sing Sing, he had a violent dispute with one of Clement Mopore's grandsons over the authorship of the poem. Surely whatever fame awaits Moore or Livingston at the solution of the mystery rests not on the merit of the poem but on its position as a perennial commonplace. Nevertheless, this indefatigable popularity was slow in developing, the momentum generating from its inclusion in widely selling anthologies of "literature by Americans" like Griswold's 1849 anthology of verse or the Duyckinck Cyclopaedia of American Literature of 1855 and in a host of Post-Civil War school readers and holiday supplements, reaching some sort of dizziness in annual costumed readings such as those conducted by Newport socialite James Van Alen, who has even added seventeen couplets of his own composition "to make the fun last longer." Besides doing much to solidify the idea of St. Nicholas as gift-giver, the Moore-Livingston poem helped fix two major modifications in the legend. First, it reduced the Saint in size, changing him from a tall, stately patron to an elf, trimming his red bishop'ws robes with white fur and giving him jolliness and twinkles where once had been dignity and composure. Second, it gave him a team of reindeer and a sleigh to replace the white horse and wagon. Moore may well claim sole responsibility for this latter development, for the idea was borrowed from a juvenile called The Children's Friend: A New-Year's Present, to Little Ones from Five to Twelve, published in New York City in 1821 one year before Harriet Butler seems to have heard the poem. Old Sante claus with much delight His reindeer drives this frosty night.

It also set his arrival date as Christmas Eve rather than St. Nicholas' Eve, although as late as the Civil War Reformed Church families waited for the Visit on

New Year's Eve, and some paintings inspired by the poem are entitled "The Night before New Year's."

|

![]() Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises

Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises