|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mark O. Hatfield, 1997 |

|

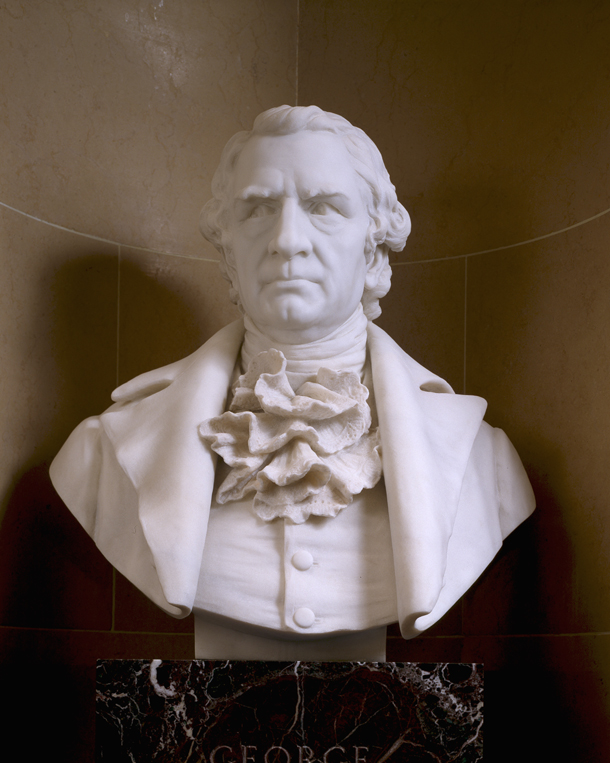

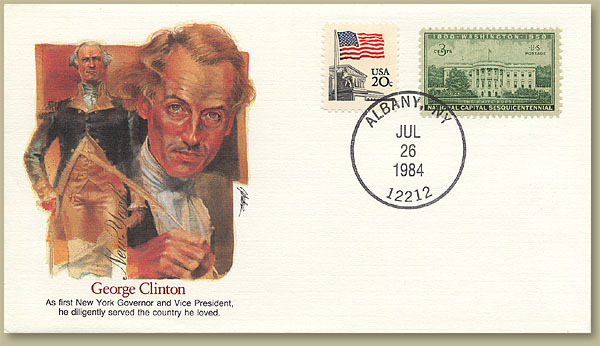

George Clinton took office as the nation's fourth vice president on March 4, 1805. He

was the second vice president to serve under Thomas Jefferson, having replaced fellow

New Yorker Aaron Burr whose intransigence in 1800 had nearly cost Jefferson the

presidency. A Revolutionary War hero who had served as governor of New York for two

decades, Clinton seemed an ideal choice to supplant Burr while preserving the New

York-Virginia alliance that formed the backbone of the Republican coalition.

Even though Republican senators may have been relieved to be rid of Burr, the contrast

between their new presiding officer and his urbane, elegant predecessor must have been

painfully apparent when Chief Justice John Marshall administered the oath of office to

Jefferson and Clinton in the Senate chamber. Jefferson offered a lengthy inaugural speech

celebrating the accomplishments of his first term, but Clinton declined to address the

members of Congress and the "large concourse of citizens" present.

Two days earlier, on March 2, 1805, Burr had regaled the Senate with a "correct and elegant" farewell oration so laden with emotion that even Clinton's friend, Senator Samuel L. Mitchill (R-NY), pronounced the scene "one of the most affecting . . . of my life." But when Clinton assumed the presiding officer's chair on December 16, 1805, two weeks into the first session of the Ninth Congress, he was so "weak & feeble" of voice that, according to Senator William Plumer (F-NH), the senators could not "hear the one half of what he says." Clinton's age and infirmity had, if anything, enhanced his value to the president, because Jefferson intended to pass his party's mantle to Secretary of State James Madison when he retired after his second term, yet he needed an honest, "plain" Republican vice president in the meantime. Clinton would be sixty-nine in 1808, too old, Jefferson anticipated, to challenge Madison for the Republican presidential nomination. Clinton had already retired once from public life, in 1795, pleading ill health. But, for all Clinton's apparent frailty, he was still a force to be reckoned with. His earlier decision to retire owed as much to the political climate in New York, and to his own political misfortunes, as to his chronic rheumatism. He had been an actual or prospective vice- presidential candidate in every election since the first one in 1788, and later capped his elective career with a successful run for the office in 1808. Clinton was, in the words of a recent biographer, "an enigma." The British forces that torched Kingston, New York, during the Revolution, as well as the 1911 conflagration that destroyed most of Clinton's papers at the New York Public Library, have deprived modern researchers of sources that might have illuminated his personality and explained his motives. Much of the surviving evidence, however, coupled with the observations of Clinton's contemporaries, support historian Alan Taylor's assessment that "Clinton crafted a masterful, compelling public persona . . . [T]hat . . . masked and permitted an array of contradictions that would have ruined a lesser, more transparent politician." He was, in Taylor's view, "The astutest politician in Revolutionary New York," a man who "understood the power of symbolism and the new popularity of a plain style especially when practiced by a man with the means and accomplishments to set himself above the common people."

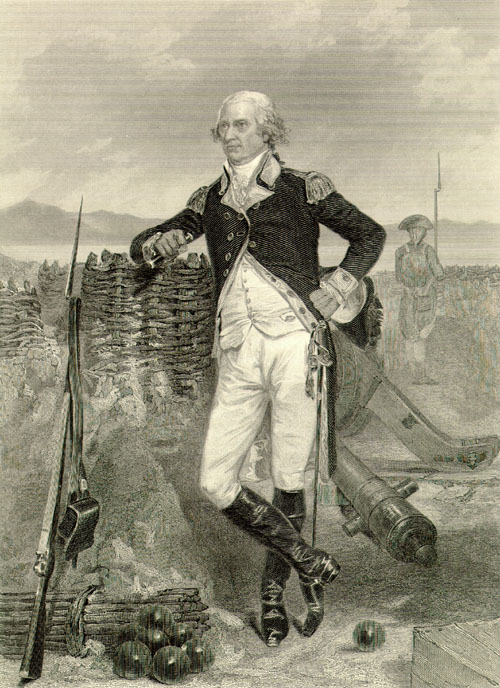

War and Politics In 1768, the twenty-nine-year-old Clinton was elected to the New York assembly, where he supported the "Livingston" faction, an alliance that he cemented two years later with his marriage to Cornelia Tappan, a Livingston relative. The Livingstons and their allies, who represented the wealthy, predominantly Presbyterian landowners of the Hudson Valley, assumed a vehemently anti-British posture as relations between England and her North American colonies deteriorated during the early 1770s. [Note: Cornelia's connection with the Livingstons was by marriage only. Her brother, Dr. Peter Tappan, was married to Elizabeth Crannell, the sister of Gilbert Livingston's wife, Catharine Crannell. Gilbert, of course, was Henry's brother.] Clinton emerged as their leader in 1770, when he defended a member of the Sons of Liberty imprisoned for "seditious libel" by the royalist majority that still controlled the New York assembly. He was a delegate to the second Continental Congress in 1775, where a fellow delegate observed that "Clinton has Abilities but is silent in general, and wants (when he does speak) that Influence to which he is intitled." Clinton disliked legislative service, because, as he explained, "the duty of looking out for danger makes men cowards," and he soon resigned his seat to accept an appointment as a brigadier general in the New York militia. He was assigned to protect the New York frontier, where his efforts to prevent the British from gaining control of the Hudson River and splitting New England from the rest of the struggling confederacy earned him a brigadier general's commission in the Continental army and made him a hero among the farmers of the western counties.

The social and political changes that the Revolution precipitated worked to Clinton's advantage, and he made the most of his opportunities. As Edward Countryman so forcefully demonstrated in his study of revolutionary New York, "the independence crisis . . . shattered old New York, both politically and socially." The state's new constitution greatly expanded the suffrage and increased the size of the state legislature. The "yeoman" farmers of small and middling means, who had previously deferred to the Livingstons and their royalist rivals, the DeLanceys, emerged as a powerful political entity in their own right, and George Clinton became their champion and spokesman. Their support proved crucial in the 1777 gubernatorial election, when Clinton defeated Edward Livingston in a stunning upset that "signalled the dismemberment of the old Livingston party." The election also signalled Clinton's emergence as a dominant figure in New York politics; he served as governor from 1777 until 1795 and again from 1801 until 1804, exercising considerable influence over the state legislation. Before leaving the battlefield to assume his new responsibilities, Clinton promised his commander in chief, General George Washington, that he would resume his military duties "sh'd the Business of my new appointm't admit of it." True to his word, he soon returned to the field to help defend the New York frontier. There, American troops under his command prevented Sir Henry Clinton (said to have been a "distant cousin") from relieving the main British force under General John Burgoyne, precipitating Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga on October 17, 1777. The Saratoga victory, which helped convince the French that the struggling colonies were worthy of the aid that proved so crucial to the revolutionary effort, marked a turning point in the war. Governor Clinton's civilian labors were equally impressive. Like other wartime governors, he was responsible for coordinating his state's war effort. New York's strategic importance and large Loyalist population, coupled with Vermont's secession in 1777, posed special problems for the beleaguered governor, but he proved an able administrator. He was increasingly frustrated, however, as war expenses mounted, and as the Continental Congress, which lacked the power to raise revenues and relied on state contributions, looked to New York to make up the shortfall that resulted when other states failed to meet their quotas. He supported Alexander Hamilton's call for a stronger Congress with independent revenue-raising powers, warning Continental Congress President John Hanson in 1781 that "we shall not be able without a Change in our Circumstances, long to maintain our civil Government." Clinton's perspective changed in 1783, after Congress asked the states to approve a national tariff that would deprive New York of its most lucrative source of income. He had long believed that Congress should facilitate and protect the foreign commerce that was so important to New York. Toward that end, he had supported Hamilton's efforts to strengthen the Articles of Confederation during the war. But the specter of a national tariff helped convince him that a national government with vastly enlarged powers might overwhelm the states and subvert individual liberties. "[W]hen stronger powers for Congress would benefit New York," his biographer explains, "Clinton would endorse such measures. In purely domestic matters, the governor would put New York concerns above all others." The governor's primary concern, according to another scholar, "was to avoid any measure which might burden his agrarian constituents wit h taxes." The tariff had supplied nearly a third of New York's revenue during the 1780s, and Clinton feared that if this critical source of income was diverted to national coffers, the state legislature would be forced to raise real estate and personal property taxes.

A Perennial Candidate for Vice President Friends of the new Constitution were much alarmed when New York and Virginia Antifederalists proposed Clinton as a vice-presidential candidate in 1788. James Madison was horrified that "the enemies to the Government . . . are laying a train for the election of Governor Clinton," and Alexander Hamilton worked to unite Federalists behind John Adams. Well-placed rumors tainted Clinton's candidacy by indicating that Antifederalist electors intended to cast one of their two electoral votes for Richard Henry Lee or Patrick Henry for president and the other vote for the New York governor. Prior to the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804, electors cast two votes in presidential elections without distinguishing between presidential and vice-presidential candidates, and the runner-up in the presidential race simply became vice president. Each elector, however, voted with the clear intent of electing one individual as president and the other as vice president. In the charged and expectant atmosphere surrounding the first election under the new Constitution, Federalists who learned of the rumored conspiracy to elect Lee or Henry president feared that a vote for Clinton would be tantamount to a vote against George Washington. Popular enthusiasm for the new government and Clinton's well-known opposition to the Constitution also worked against him. John Adams won the vice-presidency with 34 electoral votes; Clinton received 3 of the 35 remaining electoral votes that were distributed among a field of ten "favorite son" candidates. Clinton fared better in the 1792 election. By the end of Washington's first term, the cabinet was seriously divided over Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton's financial system, and all parties agreed that Washington's reelection was essential to the survival of the infant republic. In spite of their earlier reservations about Clinton, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and his Virginia allies, Madison and James Monroe, were determined to replace the "monarchist" and abrasive Vice President Adams. They considered the "yeoman politician" from New York the candidate most likely to unseat him. Clinton's candidacy faced several obstacles. He was still widely suspect as an opponent of the Constitution, and the circumstances of his reelection as governor earlier in the year had aroused the consternation of even his most steadfast supporters. John Jay, the Federalist candidate, had received a majority of the votes in the gubernatorial race, but the destruction of ballots from Federalist-dominated Otsego County on highly suspicious technical grounds by Antifederalist canvassers had tipped the balance in Clinton's favor. Jefferson worried that the New York election would jeopardize "the cause of republicanism," and Madison went so far as to suggest that Clinton should resign the governorship if he believed that he had been fraudulently elected. Even though Adams was reelected vice president with 77 electoral votes, Clinton managed to garner a respectable 50 votes, carrying Virginia, Georgia, New York, and North Carolina. The election provided a limited measure of comfort to Jefferson and Madison, who saw in the returns a portent of future success for the emerging Republican coalition. Despite his strong showing in the national election, Governor Clinton found it increasingly difficult to maintain his power base in New York. Pleading exhaustion and poor health, he announced his retirement in 1795. Although his rheumatism was by that time so severe that he could no longer travel to Albany to convene the state legislature, other factors influenced his decision. The circumstances of his 1792 reelection remained a serious liability, and his effectiveness had been greatly diminished when the Federalists gained control of the state legislature in 1793. Clinton was further compromised when his daughter Cornelia married the flamboyant and highly suspect French emissary, "Citizen" Edmond Genêt, in 1794. Clinton remained an attractive vice-presidential prospect for Republican leaders hoping to preserve the Virginia-New York nexus so crucial to their strategy, although he was never entirely comfortable with the southern wing of the party. Party strategists tried to enlist Clinton as their vice-presidential candidate to balance the ticket headed by Thomas Jefferson in 1796, but he refused to run. He soon found himself at odds with Jefferson, who became vice president in 1797 after receiving the second highest number of electoral votes. In his March 4, 1797, inaugural address to the Senate, Jefferson praised his predecessor, President John Adams, as a man of "talents and integrity." Clinton was quick to voice his outrage at this apparent "public contradiction of the Objections offered by his Friends against Mr. Adams's Election." In 1800, however, when approached by an emissary from Representative Albert Gallatin (R-PA), Clinton did agree to become Jefferson's running mate, although he seemed noticeably relieved when Republicans finally chose his fellow New Yorker, Aaron Burr, to balance the ticket.

Governor Once More Eleven years earlier, Governor Clinton had appointed Aaron Burr attorney general of New York. In 1789, with Federalists in control of the state legislature, he had been anxious to add Burr and his allies to the Clinton coalition. But he never completely trusted Burr, and his suspicions were confirmed when Burr refused to defer to Thomas Jefferson after the two candidates received an equal number of electoral votes in the 1800 presidential contest. After the furor subsided, and after the House of Representatives finally declared Jefferson the winner on the thirty-sixth ballot, Clinton's nephew and political heir, De Witt Clinton, predicted that Burr would resign the vice-presidency and try to recoup his shattered fortunes by running for governor of New York. De Witt apparently persuaded his uncle that he was the only prospective candidate who could prevent Burr from taking control of the state Republican party. George Clinton was elected governor by an overwhelming margin, carrying traditionally Federalist New York City and all but six counties. During his last term as governor, Clinton was overshadowed by his increasingly powerful and ambitious nephew. Still, although De Witt was now "the real power in New York politics," George Clinton was much revered by New York voters. Anxious to preserve the Virginia-New York coalition, but determined to limit Burr's role in his administration, Jefferson turned to Clinton for advice in making federal appointments in New York. "[T]here is no one," he assured Clinton, "whose opinion would command me with greater respect than yours, if you would be so good as to advise me." Jefferson was, in practical effect, repudiating Burr, although he never publicly disavowed or openly criticized his errant vice president. One Federalist observer soon noted that "Burr is completely an insulated man in Washington." As the 1804 election approached, De Witt wrote to members of the Republicans caucus suggesting his uncle George as a replacement for Burr.

Vice President at Last But Clinton had no intention of deferring to Madison in 1808. As Madison's biographer, Ralph Ketcham, has explained, New York Republicans were deeply jealous of the Virginians who had dominated their party's councils since 1792. "George Clinton's replacement of Burr as Vice President in 1804 was not so much a reconciliation with the Virginians," he suggests, "as a play for better leverage to oust [the Virginians] in 1808." After the election, Clinton was all but shunted aside by a president who had no wish to enhance his vice president's stature in the administration or encourage his presidential ambitions. Jefferson no longer asked Clinton's advice in making political appointments in New York or elsewhere, or on any other matter of substance, relying instead on the counsel of Madison and Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin. When he felt it necessary to consult Republican legislators, he did so in person or through Gallatin, whose Capitol Hill residence served as the meeting place for the Republican caucus. (Now known as the Sewell-Belmont House, this building still stands, adjacent to the Hart Senate Office Building.) Clinton also took little part in the social life of the administration. Washington society had a distinctly southern flavor, and, as the vice president confided to Senator Plumer, he found the "habits, manners, customs, laws & country" of New England "much preferable to the southern States." A widower for four years at the time of his election, Clinton and his daughter Maria lived frugally with House of Representatives Clerk John Beckley and seldom entertained. Even in an administration that consciously avoided ceremony and ostentatious display in favor of the simple, republican style that shocked foreign visitors and scandalized Federalists, Clinton's parsimony was legend. "Mr. Clinton, always comes to the city in his own carriage," Plumer noted. "He is immensely rich—but lives out at board like a common member—keeps no table—or invites anybody to dine. A style of living unworthy of the 2d officer in our government." Another senator observed that "Mr. Clinton . . . lives snug at his lodgings, and keeps aloof from . . . exhibitions."

Clinton's sole function was to preside over the Senate. An Ineffectual Presiding Officer Nor was he an effective presid ing officer. Senator Plumer observed, when Clinton assumed the presiding officer's chair on December 16, 1805, that he seemed "altogether unacquainted" with the Senate's rules, had a "clumsey awkward way of putting a question," and "Preserves little or no order." Senator John Quincy Adams (F-MA) shared Plumer's concern. The Senate's new president was "totally ignorant of all the most common forms of proceeding in the Senate," he wrote in his diary. "His judgement is neither quick nor strong: so there is no more dependence upon the correctness of his determination from his understanding than from his experience . . . a worse choice than Mr. Clinton could scarcely have been made." Clinton's parliamentary skills failed to improve with experience, as Plumer observed a year later: The Vice President preserves very little order in the Senate. If he ever had, he certainly has not now, the requisite qualifications of a presiding officer. Age has impaired his mental powers. The conversation & noise to day in our lobby was greater than I ever suffered when moderator of a town meeting. It prevented us from hearing the arguments of the Speaker. He frequently, at least he has more than once, declared bills at the third reading when they had been read but once—Puts questions without any motion being made— Sometimes declares it a vote before any vote has been taken. And sometimes before one bill is decided proceeds to another. From want of authority, & attention to order he has prostrated the dignity of the Senate. His disposition appears good,—but he wants mind & nerve. Although Plumer and others attributed the vice president's ineptitude to his advanced age and feeble health, Clinton's longstanding "aversion to councils" probably compounded his difficulties. He had little patience with long-winded senators, as a chagrined John Quincy Adams discovered after an extended discourse that was, by his own admission, "a very tedious one to all my hearers." "The Vice-President," he concluded, "does not love long speeches." Clinton could do little to alleviate his discomfort, given the fact that the Senate's rules permitted extended debate, but on at least one occasion he asked a special favor: "that when we were about to make such we should give him notice; that he might take the opportunity to warm himself at the fire." Clinton was frequently absent from the Senate, but he apparently summoned the strength to attend when he found a compelling reason to do so. A case in point was his tie- breaking vote to approve the nomination of John Armstrong, Jr., a childhood friend and political ally, as a commissioner to Spain. Federalist senators, and many of their Republican colleagues, vehemently opposed Armstrong's nomination, alleging that he had mishandled claims relating to the ship New Jersey while serving as minister to France. At issue was Armstrong's finding that the 1800 convention with France indemnified only the original owners of captured vessels, a position he abandoned after Jefferson insisted that insurers should also receive compensation. Senator Samuel Smith (R-MD), a member of Jefferson's own party and the brother of Navy Secretary Robert Smith, so effectively mustered the opposition forces that, by Adams' account, no senator spoke on Armstrong's behalf when the Senate debated his nomination on March 17, 1806. After Senator John Adair (R-KY) "left his seat to avoid voting," the vice president, who had earlier informed Plumer "that he had intended not to take his seat in the Senate this session," resolved the resulting 15-to-15 tied vote in Armstrong's favor. "I apprehended," Plumer surmised, that "they found it necessary & prevailed on him to attend." Clinton was absent for the remainder of the session. Clinton's only known attempt to influence legislation as vice president occurred in early 1807, when he asked John Quincy Adams to sponsor a bill to compensate settlers who had purchased western Georgia lands from the Yazoo land companies. In 1795, the Georgia legislature had sold thirty-five million acres of land to four land speculation companies, which resold the properties to other land jobbers and to individual investors before the legislature canceled the sale and ceded the lands to the United States. A commission appointed to effect the transfer to the United States proposed that five million acres be earmarked to indemnify innocent parties, but Representative John Randolph (R-VA) charged that congressional approval of the arrangement would "countenance the fraud a little further" and blocked a final settlement. In March 1806, the Senate passed a bill to compensate the Yazoo settlers, but the House rejected the measure. With sentiment against compensation steadily mounting, the Senate on February 11, 1807, enacted a bill "to prevent settlements on lands ceded to the United States unless authorized by law." The following day, Adams recorded in his diary that "The Vice-President this morning took [Adams] apart and advised [him] to ask leave to bring in a bill on beha lf of the Yazoo claimants, like that which passed the Senate at the last session, to remove the effect of the bill passed yesterday." Clinton apparently abandoned the effort after Adams responded that he did "not think it would answer any such purpose." Clinton's always tenuous relationship with Jefferson became increasingly strained as the president responded to English and French assaults on American shipping with a strategy of diplomatic maneuvering and economic coercion. Clinton viewed the escalating conflict between England and France with alarm. He believed that war with one or both nations was inevitable and became increasingly frustrated with Jefferson's seeming reluctance to arm the nation for battle. The vice president's own state was particularly vulnerable, because New York shippers and merchants suffered heavily from British raids, yet Jefferson's proposed solution of an embargo on foreign trade would have a devastating impact on the state's economy. New York's limited coastal defenses, Clinton feared, would prove painfully inadequate in the event that the president's strategy failed to prevent war.

The Election of 1808 Much to Clinton's chagrin, the caucus renominated him to a second term as vice president. His only public response was a letter to De Witt—subsequently edited for maximum effect and released to the press by the calculating nephew—denying that he had "been directly or indirectly consulted on the subject" or "apprised of the meeting held for the purpose, otherwise, than by having accidentally seen a notice." George Clinton neither accepted nor expressly refused the vice-presidential nomination, a posture that caused considerable consternation among Republican strategists. When caucus representatives called on him to discuss the matter, his "tart, severe, and puzzling reply" left them "as much in a quandary as ever what to do with their nomination of him." He was, Senator Mitchill theorized, "as much a candidate for the Presidency . . . as for the Vice Presidency." As far as Clinton was concerned, he remained a presidential candidate. While he affected the disinterested posture that early nineteenth-century electoral etiquette demanded of candidates for elective office, his supporters mounted a vigorous attack on Jefferson's foreign policy, warning that Madison, the president's "mere organ or mouth piece," would continue along the same perilous course. But Clinton, one pamphleteer promised voters, would "protect you from foreign and domestic foes." Writing under the pseudonym, "A Citizen of New-York," the vice president's son-in-law, Edmond Genêt, promised that Clinton would substitute "a dignified plan of neutrality" for the hated embargo. Turning their candidate's most obvious liability to their advantage, Clintonians portrayed the vice president as a seasoned elder statesman, "a repository of experimental knowledge." The tension between Jefferson and his refractory vice president flared into open hostility after Clinton read confidential diplomatic dispatches from London and Paris before an open session of the Senate on February 26, 1808. The president had transmitted the reports to the Senate with a letter expressly warning that "the publication of papers of this description would restrain injuriously the freedom of our foreign correspondence." But, as John Quincy Adams recorded, "The Vice-President, not remarking that the first message was marked on the cover, confidential, suffered all the papers to be read without closing the doors." Clinton claimed that the disclosure was inadvertent, but the dispatches had seemed to affirm his own conviction that "war with Great Britain appears inevitable." Much to his embarrassment, the blunder was widely reported in the press. Entering the Senate chamber "rather late than usual" one morning, Adams witnessed an unusual display of temper: The Vice President had been formally complaining of the President for a mistake which was really his own. The message of the twenty-sixth of February was read in public because the Vice-President on receiving it had not noticed the word "confidential" written on the outside cover. This had been told in the newspapers, and commented on as evidence of Mr. Clinton's declining years. He thinks it was designedly done by the President to ensnare him and expose him to derision. This morning he asked [Secretary of the Senate Samuel] Otis for a certificate that the message was received in Senate without the word "confidential;" which Otis declining to do, he was much incensed with him, and spoke to the Senate in anger, concluding by saying that he thought the Executive would have had more magnanimity than to have treated him thus. Support for Clinton's presidential bid steadily eroded as the election approached and even the most ardent Clintonians realized that their candidate had no chance of winning. Some bowed to the will of the caucus as a matter of course, while the prospect of a Federalist victory eventually drove others into the Madison camp. New England Federalists, energized by their opposition to the embargo, briefly considered endorsing Clinton as their presidential candidate but ultimately nominated Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina after intelligence reports from New York indicated that Republicans there "were disposed to unite in the abandonment of Clinton." Madison won an easy victory with 122 electoral votes; Clinton finished a distant third with only six electoral votes—a face-saving gesture by sympathetic New York Republicans, who cast the state's thirteen remaining votes for Madison. The vice-presidential contest posed a unique problem for Republican electors. Clinton was still the Republican vice-presidential candidate, notwithstanding the fact that, as Senator Wilson Cary Nicholas (R-VA) observed, his conduct had "alienated [him] from the republicans." Although painfully aware that "among the warm friends of Mr. Clinton are to be found the bitterest enemies of the administration," they ultimately elected him vice president because they feared that repudiating the caucus nomination would set a dangerous precedent. "[I]f he is not elected," Nicholas argued, "there will not in future be any reliance upon such nominations, all confidence will be lost and there can not be the necessary concert." As Virginia Republican General Committee Chairman Philip Norborne Nicholas stressed, it would be impossible to reject Clinton "without injury to the Republican cause."

The Final Term Clinton opposed Madison's foreign and domestic policies throughout his second vice- presidential term, but he lacked the support and the vitality to muster an effective opposition. Still, he dealt the administration a severe blow when he cast the deciding vote in favor of a measure to prevent the recharter of the Bank of the United States. Madison had once opposed Hamilton's proposal to establish a national bank, but by 1811, "twenty years of usefulness and public approval" had mooted his objections. Treasury Secretary Gallatin considered the bank an essential component of the nation's financial and credit system, but Clinton and other "Old Republicans" still considered the institution an unconstitutional aggrandizement of federal power. The Senate debated Republican Senator William H. Crawford of Georgia's recharter bill at great length before voting on a motion to kill it on February 20, 1811. Clinton voted in favor of the motion after the Senate deadlocked by a vote of 17 to 17. His vote did not in itself defeat the bank, since the recharter bill had already failed in the House of Representatives, but this last act of defiance dealt a humiliating blow to the administration and particularly to Gallatin, who observed many years later that "nothing can be more injurious to an Administration than to have in that office a man in hostility with that Administration, as he will always become the most formidable rallying point for the opposition." In a brief and dignified address to the Senate, Clinton explained his vote, declaring his longstanding conviction that "Government is not to be strengthened by an assumption of doubtful powers." Could Congress, he asked, "create a body politic and corporate, not constituting a part of the Government, nor otherwise responsible to it by forfeiture of charter, and bestow on its members privileges, immunities, and exemptions not recognised by the laws of the States, nor enjoyed by the citizens generally? . . . The power to create corporations is not expressly granted [by the Constitution]," he reasoned, but "[i]f . . . the powers vested in the Government shall be found incompetent to the attainment of the objects for which it was instituted, the Constitution happily furnishes the means for remedying the evil by amendment." Then-Senator Henry Clay, a Kentucky Republican, later claimed that he was the author of the vice president's remarks. Long after Clinton's death, but before Clay reversed his own position to become one of the bank's leading advocates during the 1830s, the ever-boastful Clay asserted that the speech "was perhaps the thing that had gained the old man more credit than anything else that he ever did." Clay, however, admitted that "he had written it . . . under Mr. Clinton's dictation, and he never should think of claiming it as his composition." Clinton's February 20, 1811, speech was his first and last formal address to the Senate. Two days later, he notified the senators that he would be absent for the remainder of the session. He returned for the opening session of the Twelfth Congress on November 4, 1811, and faithfully presided over the Senate throughout the winter, but by the end of March 1812 he was too ill to continue. President pro tempore William Crawford presided for the remainder of the session, while Clinton's would-be successors engaged in "[e]lectioneering . . . beyond description" for the 1812 vice-presidential nomination. On April 20, 1812, Crawford informed the Senate of "the death of our venerable fellow- citizen, GEORGE CLINTON, Vice President of the United States." The following afternoon, a joint delegation from the Senate and the House of Representatives accompanied Clinton's body to the Senate chamber. He was the first person to lie in state in the Capitol, for a brief two-hour period, before the funeral procession escorted his remains to nearby Congressional Cemetery. President Madison was among the official mourners, although he and the first lady held their customary reception at the Executive Mansion the following day. In the Senate chamber, black crepe adorned the presiding officer's chair for the remainder of the session, and each senator wore a black arm band for thirty days "from an unfeigned respect" for their departed president. Clinton's former rival, Gouverneur Morris, later offered a moving—if brutally frank—tribute to the fallen "soldier of the Revolution." Clinton had rendered a lifetime of service to New York and the nation, Morris reminded his audience, but "to share in the measures of the administration was not his part. To influence them was not in his power."

|

NAVIGATION |

|

|

![]() Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises

Copyright © 2003, InterMedia Enterprises